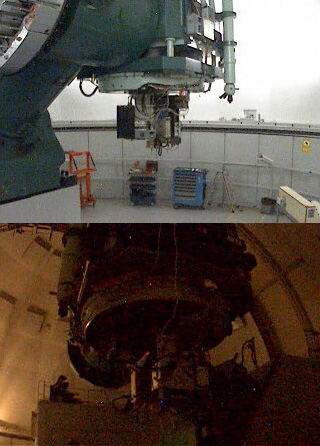

| My DLR colleague Stefano Mottola and I perform an observation campaign of the irregular satellites of Jupiter to measure lightcurves for rotation period, spin-axis orientation, and shape determination. For this task, we use the 1.23-m telescope at Calar Alto in southern Spain which allows us to observe the largest of Jupiter’s outer moons in greater detail. | Mein DLR Kollege Stefano Mottola und ich führen eine Beobachtungskampagne der irregulären Jupitermonde durch, um Lichtkurven zur Bestimmung der Rotationsperioden, Polachsenausrichtungen sowie der Formen der Objekte zu erhalten. Für diese Aufgabe verwenden wir das 1.23-m Teleskop auf dem Calar Alto in Südspanien, mit dem wir die größten der irregulären Jupitermonde im Detail studieren können. |

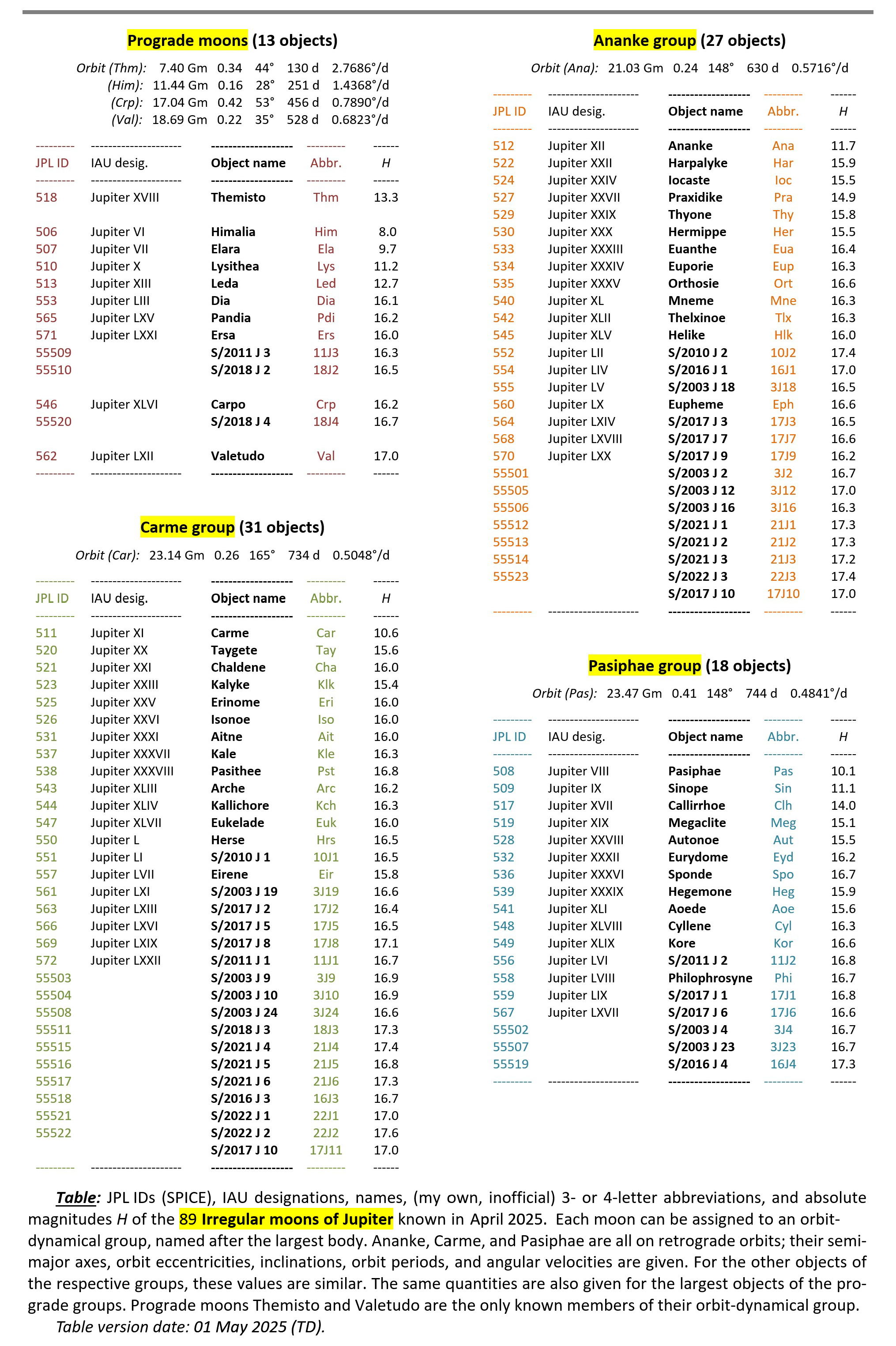

As of 01 May 2025, 97 moons of Jupiter have been announced: The 4 large Galilean moons, 4 small inner moons, and 89 outer or irregular moons. Since new discoveries have been made recently, and more will likely be done in the near future, please check for up-to-date information here (english Wikipedia on Moons of Jupiter) or here (JPL SSD website).

Links to individual Jovian Irregular-moon pages:

• (544) Kallichore

![]() ← List of giant planet moons: Numbers, names, TD abbreviations, SPICE/JPL IDs (.txt file)

← List of giant planet moons: Numbers, names, TD abbreviations, SPICE/JPL IDs (.txt file)

Paper on Himalia’s rotation period:

• Pilcher, F., Mottola, S., Denk, T. (2012): Photometric Lightcurve and Rotation Period of Himalia (Jupiter VI). Icarus 219, 741-742. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.03.021.

Paper on Cassini’s Jupiter flyby in Dec 2000, including observations of Himalia:

• Porco, C.C., 23 colleagues (2003): Cassini Imaging of Jupiter’s Atmosphere, Satellites, and Rings. Science 299, no. 5612, 1541-1547. doi:10.1126/science.1079462.

• Another source for this paper is here.

• An excerpt of the part describing the Himalia findings can be found here.

Images of Himalia and Elara:

• from Cassini (Dec 2000): Himalia

Notes: Label at left: date and time (UTC); on top: filter names; at bottom: effective filter wavelengths [nm].

• from New Horizons (Feb 2007): Himalia; Elara

Notes: Top row: 1x zoom; middle row: 5x zoom; bottom row: 5x zoom interpolated.

Jovian satellite discoveries:

• Himalia discovery: Harvard College Observatory Astronomical Bulletin no. 173 (06 Jan 1905)

• Elara discovery: Harvard College Observatory Astronomical Bulletin no. 178 (27 Feb 1905)

Jovian satellite naming and overview lists:

• J1 (Io) to J4 (Callisto): Marius, S. (1614): Mundus Iovialis (part relevant to modern naming; in Latin and German)

• J1 (Io) to J4 (Callisto): Marius, S. (1614): Mundus Iovialis (part relevant to modern naming; in Latin and German)![]()

• J5 (Amalthea) to J13 (Leda): IAU circ. no. 2846 (07 Oct 1975)

• J14 (Thebe) to J16 (Metis): IAU circ. no. 3872 (30 Sep 1983)

• J17 (Callirrhoe) to J27 (Praxidike): IAU circ. no. 7998 (22 Oct 2002)

• J28 (Autonoe) to J38 (Pasithee): IAU circ. no. 8177 (08 Aug 2003)

• J39 (Hegemone) to J48 (Cyllene): IAU circ. no. 8502 (30 Mar 2005)

• J49 (Kore): IAU circ. no. 8826 (05 Apr 2007)

• J50 (Herse): IAU planetary naming news (09 Nov 2009)

• J53 (Dia): IAU planetary naming news (10 Mar 2015)

• J62 (Valetudo): IAU planetary naming news (03 Oct 2018)

• J57 (Eirene), J58 (Philophrosyne), J60 (Eupheme), J65 (Pandia), J71 (Ersa): IAU planetary naming news (19 Aug 2019)

• An overview of names and absolute magnitudes of the Jovian irregular moons is given in the screenshot here. (Does not include at least 57 additional objects without known orbits.)

• Johnston’s Archive provides orbital and dynamical data as well as physical data for all solar system planets and satellites.

Planning-related webpage and observatory information:

• JPL’s HORIZONS Web-Interface

A list of select spacecraft ID codes for HORIZONS can be found here.

• Ground-based observatory:

Calar Alto 1.23-m telescope [HORIZONS ID code 493] — 357°27’15.1″ E, 37°13’24.7″ N, 2173.1 m altitude

Calar-Alto related webpages:

• Weather forecast (continuous live data stream)

• Weather forecast (continuous live data stream)

• Current Meteosat weather picture

• Calar-Alto webcams (continuous live data stream); the WEST, Southwest and NORTH views show the dome of the 1.23-m telescope

• Observers timeline for fall 2024 and spring 2025

Table: Physical and astronomical properties of the 11 largest irregular moons of Jupiter (H < 15 mag) and Kallichore

| Moon | JPL ID (1) | Orbit (2) | Apparent magnitude [mag] (3) |

Absolute magnitude H [mag] (4) |

Visible albedo range [%] (5) |

Mean diameter [km] (5) |

Rotation period [h] (6) |

Semi-major axis [million km] (7) |

Eccentricity [ ] (7) |

Inclination [deg] (7) |

Orbital period [d] (7) |

Moon (abbrev.) (8) |

| Themisto | 518 | prograde | 21.0 | 13.3 | 6 ? | ∼9 | ? | 7.40 | 0.34 | 44 | 130.0 | Thm |

| Himalia | 506 | prograde | 14.8 | 8.0 | 4.9–6.5 |

x

|

|

11.44 | 0.16 | 28 | 250.6 | Him |

| Elara | 507 | prograde | 16.6 | 9.5 | 3.9–5.3 | 80 | ? | 11.71 | 0.21 | 28 | 259.6 | Ela |

| Lysithea | 510 | prograde | 18.2 | 11.1 | 3.0–4.2 | 42 | (12.8) | 11.70 | 0.12 | 27 | 259.2 | Lys |

| Leda | 513 | prograde | 20.2 | 12.6 | 2.8–4.0 | 22 | ? | 11.15 | 0.16 | 29 | 240.9 | Led |

| Pasiphae | 508 | retrograde | 16.9 | 10.2 | 3.8–5.0 | 58 | ? | 23.47 | 0.41 | 148 | 743.6 | Pas |

| Carme | 511 | retrograde | 17.9 | 10.9 | 2.9–4.1 | 47 | (10.4) | 23.14 | 0.26 | 165 | 734.2 | Car |

| Sinope | 509 | retrograde | 18.3 | 11.3 | 3.6–4.8 | 35 | (13.2) | 23.68 | 0.26 | 157 | 758.8 | Sin |

| Ananke | 512 | retrograde | 18.9 | 11.8 | 3.2–4.4 | 29 | (8.3) | 21.03 | 0.24 | 148 | 629.8 | Ana |

| Callirrhoe | 517 | retrograde | 20.8 | 14.0 | 3.6–6.8 | 10 | ? | 23.80 | 0.30 | 145 | 758.9 | Clh |

| Praxidike | 527 | retrograde | 21.2 | 14.9 | 2.3–3.5 | 7 | ? | 20.94 | 0.25 | 148 | 625.4 | Pra |

| Kallichore | 544 | retrograde | 23.7 | 16.3 | 4 ? | ∼3½ ? | ? | 23.02 | 0.25 | 165 | 728.3 | Kch |

Table notes:

(1)…JPL’s SPICE is a commonly-used information system of NASA’s Navigation and Ancillary Information Facility (NAIF). It assists engineers in modeling, planning, and executing planetary-exploration missions, and supports observation interpretation for scientists. Each planet and moon obtained a unique SPICE number.

(2)…The irregular satellites of Jupiter can be subdivided into objects with prograde and objects with retrograde orbits. Themisto is the irregular moon closest to the planet. The moons in the prograde Himalia group share an inclination close to 28°. The retrograde irregulars orbit Jupiter in three distinct groups at inclinations ranging from ∼145° to ∼165°. The naming convention is that all prograde irregular moons of the Himalia group have names ending with an ‘a’, the other prograde irregulars have names ending with ‘o’, and the retrograde moons’s names end with an ‘e’.

(3)…Apparent magnitude as seen from Earth (R-band); from S. Sheppard’s Jupiter satellites website. Smaller numbers indicate brighter objects. The magnitude scale is logarithmic, with an object of 6th mag being 100x darker than a 1st mag object. The human eye can spot celestial objects down to ∼6th magnitude.

(4)…The absolute magnitude is the magnitude (brightness) of an object if located 1 au away from the sun and observed at 0° phase angle (i.e., the observer virtually sits at the center of the sun in this definition). Smaller numbers again indicate brighter objects. The H values listed here were taken from Table 1 of the paper of Grav et al. (2015) who refers to Rettig et al. (2001). The Themisto, Callirrhoe, Praxidike and Kallichore values are from MPEC. Be aware that different sources list quite different values for H; e.g., compare with values from MPEC, a NASA Fact Sheet, JPL’s ssd page, S. Sheppard, or Table 12.1 in Jewitt et al. (2004) (which has the same values as the Sheppard site).

(5)…Albedos and diameters are from WISE and NEOWISE data published in Table 3 of Grav et al. (2015). The axes of Himalia are from our Cassini work, published in Porco et al. (2003). The Themisto diameter is again from S. Sheppard (and might well be underestimated); the Themisto albedo is just a guess. The Kallichore albedo is a guess based on Carme’s, with the corresponding diameter taken from this table.

(6)…All values are synodic rotation periods. The Himalia value is from our Pilcher et al. (2012) paper. The Lysithea, Sinope, Carme, and Ananke periods are from Luu (1991). Because of the short observation timelines, they are likely inaccurate and thus notated in brackets only. Luu (1991) also observed Elara, Pasiphae, and Leda, but could not deduce periods.

For Elara, JPL’s HORIZONS Web-Interface gives ∼0.5 d, but I could not find a proper source from where they got it. Maybe it was taken from Table 6.1 in Stanton Peale’s chapter in the 1977 Planetary Satellites book of the University of Arizona Press? If so, it would definitely be wrong because all unknown periods in this table are listed as “0.5 d”. Thus, no Elara rotation period is added to my table here.

Leda was observed by Rettig et al. (2001) over three consecutive nights, but they could not extract a rotation period. They thus note ∼24 h as a possible value for Leda, but I do not believe that because a non-detection of a period does not necessarily point to a period close to Earth’s. It may also mean that the equatorial cross-section of the object is rather spherical with no prominent albedo markings, that the object’s pole axis was pointing close to the observer, that the rotation itself is very slow, or that the observation’s signal-to-noise ratio was insufficient.

(7)…The data for the orbital parameters were taken from JPL SSD (May 2025).

(8)…These abbreviations are my own and not official.

© Tilmann Denk (2025)